h3. Introduction

This article discusses copyrights, particularly from the perspective of web designers.

h4. Some introductory notes:

* *The usual disclaimers apply:* This is not legal advice, and does not create an attorney-client relationship. Any legal situation is highly fact-dependent, etc.

* *No warranty:* I’ve tried my best to be accurate and clear, but give no warranty on any of this information. Use at your own risk, and your mileage my vary.

h4. Scope notes:

* *It’s an article, not a treatise.* Entire books have (and will continue to be) written on these topics and other related subjects, and this article is but an introduction to them.

* *United States only.* The scope of this article is limited to the U.S. Of course, copyright is an international topic, but I’m more confident talking about it as to the U.S.

* *Copyright only.* This article won’t discuss any other kinds of intellectual property, including patents, trademarks, trade secrets, etc.

* *Other topics:* Some topics outside the scope of this article include: whether to register your copyright(s), the intricacies of “Creative Commons”:http://creativecommons.org/ licensing, educational uses (remember class packets?), and how best to respond when someone copies your copyrighted material. Perhaps in a future article…

h4. In The Beginning:

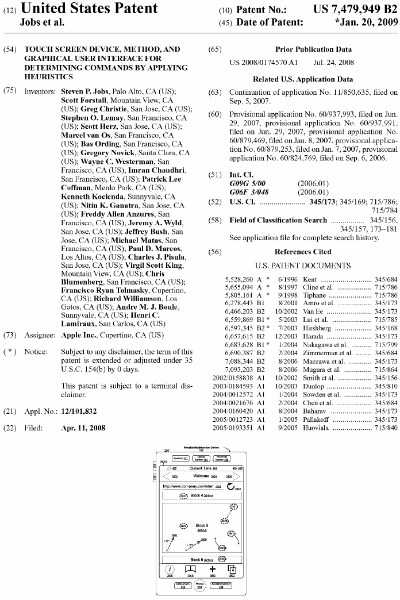

Copyright law in the U.S. originates with the “Constitution”:http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/constitution.html. The image above shows Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, which grants Congress the power:

bq. To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries “1”:http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/constitution_transcript.html

h3. You Created It; You Own It

The term “copyright” refers to a bundle of property rights granted by law to the creators of “original works”. The property rights arise immediately, when the original work is “fixed in a tangible form of expression”. In other words, the copyright is created when you save it on your hard drive, not when you post it.

So, when you originate that great story/article/song/play/blog post/movie script, and you write/design/draw/photograph/illustrate/record/compose it on your pad of paper/notebook/Moleskine/computer/PDA, a copyright is born.

h4. Questions, already:

* “I borrowed some inspiration from…” *Originality is required.* If you copy someone else’s original work, you have no copyright. Indeed, you’ve infringed their copyright, unless you fit within an exception. If you start with their work and make additions and changes, you’ve created a “derivative work.” (Derivative works may be discussed in a later article.)

* “But it wasn’t published yet” *Publication is _not_ required.* Since 1978, the copyright exists when an original work is fixed in a tangible medium, whether it’s published or not.

* “But there’s no (c) symbol” *A copyright notice is also not required.* (More on notices later in this article.)

* “But it’s not registered” *Copyright registration is also not required.* Though it can be beneficial, and is required eventually if you want to sue someone for copyright infringement. (Again, perhaps in a later article.)

h4. Exceptions, already:

* *Agreements:* An agreement by the creator of the work to sell/license/transfer rights in that work, changes things. (Surprising, I know.) Some examples include employment agreements, consulting contracts and “work for hire” agreements.

* *Owning a Copy:* If you buy a book, or CD, or DVD, you own that copy. But you do not own the copyright to the text, music or video. A simple example is that you can sell your copy of a book, but you can’t reproduce and sell copies of the book.

* *Non-Commercial Use:* There is no exception for non-commercial copyright infringement. It’s up to the copyright owner to decide whether they want your “free advertising.” However, this can be considered as one of the factors of an exception called “fair use”…

* *Fair Use:* There _is_ an exception for short quotes to enable commentary, criticism or parody. However, this is fairly complicated, and highly dependent on the specific fact situation. (More on fair use later.)

h3. What Are My Rights?

The owner of a copyright in an original work has the exclusive right to:

* *Publish* it.

* *Reproduce* it.

* *Distribute* it.

* *Display* it.

* *Make “derivative works.”*

* *Perform* it (in the case of music, plays, movies, etc.)

h3. Are There Limits On My Rights?

One of the exceptions to copyright is called “fair use,” under which some of a copyrighted work may be quoted or reproduced for the purpose of commentary, criticism, journalism, education, research, or parody.

*Caution:* Fair use is complex. The boundaries are very fuzzy, and clear rules are hard to find.

Some factors to be considered in evaluating whether fair use applies:

# the purpose and character of the use, including commercial or nonprofit educational purposes;

# the nature of the copyrighted work;

# amount and relative significance of the portion, compared to the entire copyrighted work; and

# the resulting effect on the market for or value of the copyrighted work. “2”:http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html

*Caution (Again):* From the Copyright Office circular entitled “Fair Use”:http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html (of course):

bq. The distinction between “fair use” and infringement may be unclear and not easily defined. There is no specific number of words, lines, or notes that may safely be taken without permission. Acknowledging the source of the copyrighted material does not substitute for obtaining permission.

*Summary:* Evaluating fair use is tricky. When in doubt, try asking the copyright owner for permission.

h3. What Is Not Copyrightable?

Some kinds of materials or otherwise “original works” cannot be copyrighted. The following quotes are examples from the Copyright Office circular entitled “Copyright Basics”:http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ01.pdf, in the section entitled “What Is Not Protected By Copyright?”:

bq. Titles, names, short phrases, and slogans; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering, or coloring; mere listings of ingredients or contents

*For example:* you don’t own “white on dark” text, or a “green and black” color scheme, or the slogan “Web Standards Rule” or “Web Wizards,” or similar short phrases and general ideas.

*Exception:* Remember that we are *not* talking about trademarks here. Maybe in a later article.

bq. Ideas, procedures, methods, systems, processes, concepts, principles, discoveries, or devices, as distinguished from a description, explanation, or illustration

*Summary:* Copyright is all about the _expression_ of an idea, not the idea itself. A specific “wicked worn” website design may be copyrighted, but you can’t copyright the _idea_ of “scuffing up your graphics.”

bq. Works consisting _entirely_ of information that is common property and containing no original authorship (for example: standard calendars, height and weight charts, tape measures and rulers, and lists or tables taken from public documents or other common sources)

*Summary:* Remember that term “original works” from up at the top of this article? It has to be original to be copyrightable.

At the risk of talking from both sides of my mouth, the standard for “originality” is relatively low. For example, you might think that the latest in a grand tradition of a hundred thousand romance novels is not sufficiently original to merit copyright protection, but as long as the author didn’t plagiarize or copy….

h3. After You Post It, You Still Own It

When you post your own copyrighted material on the internet, you still have the copyright. You haven’t given it away, and it doesn’t become public domain, and it’s _not_ okay for someone to copy it. Remember the discussion about owning a book, but not its copyright.

Just in case there’s any doubt though, you _have_ published it.

h3. Copyright Notices

A copyright notice is the cryptic little phrase at the bottom of many websites, inside the cover of every book, etc. It is basically a statement that “I own this original work.”

The correct form includes three items:

# The word “copyright” or “copr.”, or the (c) symbol.

# The year of first publication of the copyrighted material to which the notice refers.

# The name of the copyright owner. This may be an individual’s full name or last name only, or a company or organization name (or a recognizable abbreviation).

This third one causes some confusion for websites (and software programs, like Windows for example), which contain various chunks of material that were posted/published in different years. The usual solution is the “year1-year2” nomenclature.

By the way, it is generally considered acceptable to change the order of these three items of a copyright notice, although it looks funny if the copyright word/symbol isn’t in the front.

h4. Some examples:

* copyright 2006 John Doe

* (c) 2006 Doe

* (c) Doe & Co. 2005-2006

* copr. 2005 Doe Community Church

h4. Notes on Notices:

You may see a notice that includes the phrase “all rights reserved.” This is an artifact from a time when a few countries actually concluded that a copyright notice did _not_ necessarily indicate an intention to reserve all rights, only some of them. My understanding is that this phrase is no longer necessary at all.

By the way, you may also see the characters “( C )”. This is simply incorrect. These three characters have never been given legal effect.

h4. Copyright Notice No Longer Necessary

The copyright notice is now optional, at least in all countries that have ratified the Berne Convention. However, it can be beneficial.

h3. Lifetime Of A Copyright:

That word “lifetime” is a little joke, because the copyright in current works lasts for the lifetime of the creator, plus _70 years._ *Short answer:* long enough.

h3. Don’t Infringe Copyrights

At the very least, it’s illegal. As a Christian, it’s also a poor witness. Consider “Thou shall not steal.”

h3. Rules of Thumb on the Internet:

These are only rough guidelines, but they’re good ones:

* If it’s on the internet, it’s copyrighted.

* If you didn’t originate it, you don’t own the copyright.

* When in doubt, ask for permission.

* Or be certain as to fair use (and cite the original author).

* Or look for works available under a creative commons license.

* Don’t infringe copyrights.

h3. Additional Resources:

h4. “United States Copyright Office”:http://www.copyright.gov/

# “Copyright Basics”:http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ01.pdf

# “Summary of Fair Use”:http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html

# “Information Circular 3 – Copyright Notice”:http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ03.html

h4. Summaries:

# “Wikipedia”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright also has some copyright information.

h4. University Resources:

# “Stanford University’s Copyright & Fair Use Overview”:http://fairuse.stanford.edu/Copyright_and_Fair_Use_Overview/

# “Cornell’s Legal Information Institute – Copyright”:http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/index.php/Copyright

# “Purdue University Copyright Office – Copyright Basics”:http://www.lib.purdue.edu/uco/basics/

# ” Purdue University Copyright Office – Copyright Exemptions”:http://www.lib.purdue.edu/uco/exemptions/ (at least the first “Fair Use” section)

h4. Multimedia and Internet:

# “An Intellectual Property Law Primer for Multimedia and Web Developers”:http://www.eff.org/Censorship/Academic_edu/CAF/law/multimedia-handbook

at “Electronic Frontier Foundation”:http://www.eff.org/. A formatted version is posted at: “An Intellectual Property Law Primer for Multimedia and Web Developers”:http://www.nationaltechcenter.org/legal/webcopyright.asp

# “10 Big Myths About Copyright Explained”:http://www.templetons.com/brad/copymyths.html (by Brad Templeton, Chairman of the Board for the “Electronic Frontier Foundation”:http://www.eff.org/)

# “A brief intro to copyright”:http://www.templetons.com/brad/copyright.html

# “Getting Permission to Publish: Ten Tips for Webmasters”:http://www.nolo.com/article.cfm/catId/D067F3DC-202E-4EF7-AAEEEFB60061533D/objectId/8CD796F2-9770-4ECA-B8F2B4F66DB170F1/310/266/ART/

(talk about a messy URL!) Good article for web publishers.

h4. From Nolo Press:

# “Nolo Press Copyright page”:http://www.nolo.com/resource.cfm/catID/DAE53B68-7BF5-455A-BC9F3D9C9C1F7513/310/276/ (Lots of good information, at about the correct level of sophistication.)

# “When Copying Is Okay: The ‘Fair Use’ Rule”:http://www.nolo.com/article.cfm/catId/DAE53B68-7BF5-455A-BC9F3D9C9C1F7513/objectId/C3E49F67-1AA3-4293-9312FE5C119B5806/310/276/ART/

_This article is (c) Montgomery 2006. Some rights released with a_ Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

_Also published at_ “Godbit”:http://godbit.com/article/copyright.

_Photo excerpt of the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8, from the_ “National Archives”:http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/constitution.html.